The Painted portrait and photography

John Berger’s essay, The Changing View of Man in the Portrait (1969), opens with the assertion that it is "unlikely that any important portraits will ever be painted again." Berger observes that the decline of the painted portrait coincided with the rise of photography. He believes that the mechanical and democratic nature of the photograph “offered the opportunity of portraiture to the whole of society," thereby rendering the professional practice of painted portraiture as outdated. While the development of the photographic enterprise has played a significant role in shaping our contemporary culture, I do not fully support the claim that photography can serve as an appropriate substitute for the painted portrait. Berger’s argument overlooks the photograph’s subjectivity and its ability to idealise and distort a likeness. The argument also fails to address the fundamental dynamic of seeing central to photography, as well as the difference in interpreting originals and reproductions. The way we use photographs in a contemporary context contrasts significantly with the period when John Berger wrote his essay. Photographs have become far more invasive in the immense volume that we consume them, and the act of taking images now carries an unsettling, inherent aggression. In a society where an overwhelming quantity of photographs pollutes our media, there is a growing position for a more singular, idealistic painted representation of the human likeness.

Before the chemical fixing of the photograph, the painted portrait was the only means of recording a likeness that could outlast the subject it represented (Berger, 1969). Traditionally, the art of portraiture was reserved for the wealthy and aristocracy as a confirmation of social status. Having one’s likeness depicted was a privilege inaccessible to most of society. With the invention of photography, the human likeness could be delivered at a lower cost and with a faster production rate (West, 2004). As a result, professional photographers embraced the lucrative trade of portraiture and transitioned from the traditional painted mediums. It is reasonable in an essay written before the digital age for Berger to conclude that photography is a superior means of conveying a likeness. A photograph possesses a quality of evidence that is often perceived as true. The perception of a photograph comes with a perpetual contact with the subject. Viewing the likeness of a deceased loved one can evoke a similar connection to seeing them in life. There is a commonality between perceiving a photograph and our experience of the surrounding world, enabled by the accuracy and realism offered by a camera (Currie, 1991). In this sense, photography can be superior to painted portraits. However, to consider a photograph as “psychologically revealing” (Berger, 1969) or as an objective record overlooks the camera’s ability to idealise, distort, and deceive a likeness influenced by the photographer's subjectivity. In a later essay by John Berger, Ways of Seeing, 1972, he contradicts his earlier stance by emphasising the role of perspective.

Like a painting, a photograph is contained within the boundaries of the frame. It comes with no context concerning what exists beyond it. The choice of subject and selective composition reflects the photographer’s unique way of seeing (Berger, 1972). Moreover, our appreciation and interpretation of the same photograph depend on our individual beliefs and perspectives. Therefore, it is impossible for a photograph to exist as an objective document; rather, it is a picture of perspective, illustrating how a subject was perceived. Although a painting is also crafted with the artist’s intention, the interaction we have with it differs significantly from how we perceive a photograph. When comparing painting and photography, it is crucial to distinguish between the significance of reproductions and originals. A painting is original in that it can only exist in one place at a time (Berger, 1972). The singularity of a painted portrait endows it with authority and value, more accurately reflecting the way we perceive our surroundings. The human eye, similarly, can be only in one place at a time. The eye takes appearances with it, and fleeting images are destroyed just as they are created. The eye is the original that the camera aspires to replicate. Our perception of the surrounding world encompasses context, space, and a sense of time. In contrast, a photograph is devoid of such qualities. When a camera captures an image, the scene is reduced to a static representation that becomes reproducible and transportable (Sontag, 1977). Suddenly, an individual’s likeness can be perceived across an infinity of contexts, in any location at any time. This manipulation of self-presentation and expression diminishes the value of the portrait through the material form of the photograph.

A contemporary and contrasting position to Berger’s claim is that of Cynthia Freeland. In her publication, Portraits and Persons: A Philosophical Inquiry (2010), Freeland defines a portrait as:

“a visual depiction of a living being as a unique individual, by means of an individually recognisable visage and an expression of inner life, implying a sense of self-identity, where the subject is complicit in the project and, at best, presented through the subject’s individual ‘essence’ or ‘air’.”

For Freeland, the self-presentation of the sitter is of vital importance to a successful portrait. This argument disqualifies any candid photograph of a person as a portrait. If a person is unaware of their image being taken, then it is impossible for their true self-identity to be honoured (Maes, 2017). In addition, Freeland states that the subject must be complicit in the taking of the image. In the practice of photographic portraiture, it is rare for this agreement between the photographer and model to occur. Whereas a painting is often created to dignify a subject, through a romantic notion the portrait photographer is positioned as the creative master, dominating and navigating a scene. The subject or model is rarely mentioned or considered in the presentation of the work. The self-presentation of the sitter is made redundant and, therefore, could not be considered a portrait.

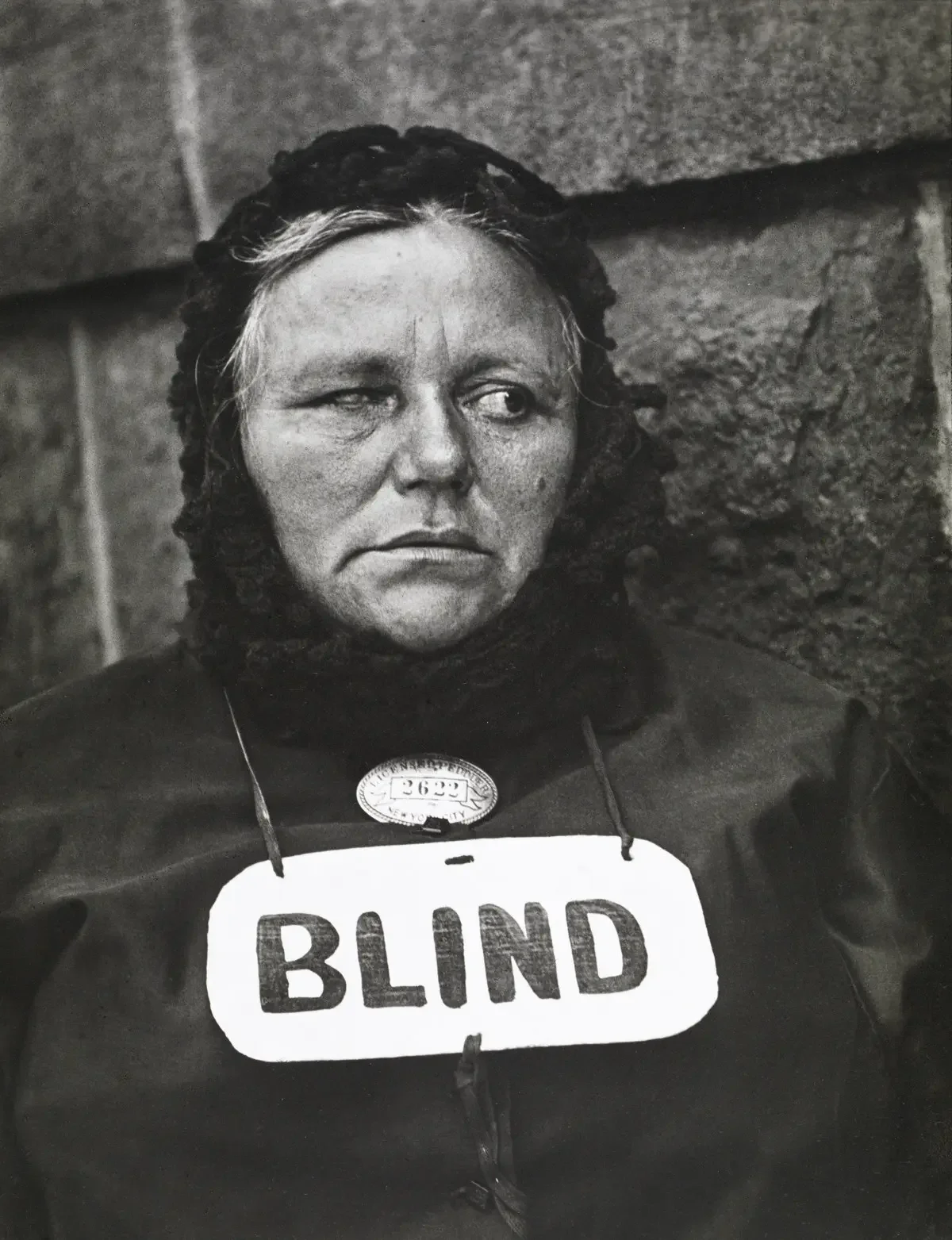

Blind Woman, Paul Strand 1917

Take, for example, the photograph Blind Woman by early photographer Paul Strand. A pioneering member of the straight photography movement, he employed a technique of attaching a false lens to the side of his camera as a means to create candid photographs. (Paul Strand: Master of Modern Photography, n.d.) With this method, Strand aimed to capture people without their awareness or ability to pose for their image. Not only does this practice deny the individuality of the subject, but it also violates the person's right to express themselves. This spontaneity and candid quality have become an institutionalised practice in portrait photography, even in a modern day context.

Bruce Gilden, New York City

The work of contemporary street photographer Bruce Gilden also relies on invading people’s space and observing their reactions. An image of someone in a temporary state of shock or annoyance does not reflect their true nature and would therefore not constitute a portrait (Freeland, 2010). There is an inherent aggression in taking images of people. To photograph someone is to possess and distort their likeness. (Sontag, 1977)

Rembrandt Van Rijn

By contrast, the painted portrait has remained a way to confer importance to an individual. The portraits by Dutch painter Rembrandt Van Rijn above display an adoration and respect for the subject matter. In the painted picture, the artist’s reference is the presentation of the sitter’s self (Freeland, 2017). When the portrait is created, there is a contribution from both the model and the artist. The resulting depiction is a portrait that reflects a collaboration and, therefore, is more successful at representing the individual than any snapshot photograph.

In 2025, it is estimated that over 2.1 trillion photographs will be taken (Broz, 2025). Our culture and beliefs are built on images. The world and everything within it exist as a collection of photographs (Sontag, 1977). Photography has become so pervasive in modern life that images shape our perceptions of reality. They construct narratives, reinforce societal norms, and inform ideologies. Our identities and the beliefs we subscribe to have been commodified, constantly marketed to us through tailored algorithms and images of human likeness. The overwhelming quantity of photographs we are subjected to diminishes the value of portraits and fosters a voyeuristic detachment from our own likeness. The overconsumption of media has led to desensitisation, where the singular image no longer holds the same emotional impact. In response to this, there is a growing awareness and demand for the preservation of our identity. Berger concludes by stating, “that the demands of a modern vision are incompatible with the singularity of viewpoint which is a prerequisite for a static-painted likeness.” It is with irony that modernity has led us now to appreciate such a singularity to combat a culture where appearances have become disposable. The painted portrait continues to hold significance even in a society dominated by photographic media. A painting offers an idealised likeness that embodies intention and permanence and is immune to the manipulation of being reproduced. Today, the value of the painted portrait comes with its singularity and originality.

I disagree with John Berger’s claim that it is "unlikely that any important portraits will ever be painted again." At its inception, photography offered an alternative means for professional portrait artists to produce a likeness. It was quicker, more accurate, and came at a much lower cost. It is understandable why John Berger believed that photography would eventually replace painted portraits, as the technical accuracy of a mechanical device outdates the more traditional mediums. However, Berger’s expectations of photography did not hold to be true in a contemporary context. The camera, as merely a looking device, can also idealise and distort appearances in the eyes of the beholder. The informative quality of a photograph becomes redundant when the intention of the photographer is to deceive. In the realm of portraiture, much of photographic art history fails to honour or represent the self- presentation of the sitter. The inherent possessiveness of taking photographs stands in contrast to the collaboration found in a painted portrait between the model and the observer. With their ability to capture only a unique moment in time, photographs are only capable of portraying a narrow representation of one’s personality.

In contrast, paintings are constructed over time with reference to the individual. Finally, the value of photographic portraits has diminished due to the overwhelming quantity and consumption of images. We have become passive observers, desensitised to our own likeness, and consequently feel a lesser connection to singular photographs. It is for these reasons that there is a rising demand for painted portraits. Photographs will continue to shape our culture and remain fundamental to the documentation of humanity. However, I strongly believe that the painted portrait will be revived through a romanticised movement in response to post-modern media consumption.

Berger, J. (2001). The Changing View of Man in the Portrait [The Changing View of Man in the Portrait]. Selected Essays- Dyer,G., 98–102.

Berger, J. (1972). Ways of Seeing. Penguin.

Sontag, S. (1977). On Photography. Allen Lane.

Freeland, C. (2007). Portraits in painting and photography. Philosophical Studies, 135(1), 95–109. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-007-9099-7

West, S., & Netlibrary, I. (2004). Portraiture. Oxford University Press

Brook, D. (1983). Painting, Photography and Representation. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art

Criticism, 42(2), 171–180. https://doi.org/10.2307/430661

Maes, H. (2020). Portraits and philosophy. Routledge.

Maynard, P. (2011). Portraits and Persons: A Philosophical Inquiry. The British Journal of Aesthetics, 51(4), 449–453. https://doi.org/10.1093/aesthj/ayr027

Maes, Hans, Conversations on Art and Aesthetics (Oxford University Press, Incorporated, 1st ed, 2017)

Paul Strand: Master of Modern Photography. (n.d.). Philamuseum.org. https://philamuseum.org/calendar/exhibition/paul-strand-master-of-modern-photography