Reflections on Postsructuralism & semiotics

When telling a story or taking an image, there is a displacement from the time and place where the events first occurred or appeared. When the event is narrated or its likeness preserved, it is given form and becomes readable. When reading, we do so with reference to our own lived experience, as our seeing is deeply entangled with our knowing. The author also writes from experience and assumes that their audience will relate in the same way. Despite our interpretations being vast and individual, the enterprise of visual arts and literature has long depended on the intentions and history of those who authored the works (Barthes, 1967). In The Death of the Author, Roland Barthes dismantles the archetype of the author, posed as a modern invention of capitalist ideology. Barthes speaks of the many voices present in art that inform the creation of any given work, voices that lose their origin and cultural relevance when the works are attributed to a single originator. In recognising the intertextuality within the arts, meaning becomes unstable, and interpretation is democratised. Barthes’ theory, which advocates for the plurality of meaning, emerged from Poststructuralism. A philosophical movement responding to the preceding structuralists. The movement rejects the notion of fixed meanings and meta-narratives within social constructs. Although primarily an intellectual movement, Poststructuralism laid the foundation for Postmodernism, the aesthetic and cultural response that displayed scepticism towards universal truths and allowed for subjectivity and diversity of perspective (Chandler, 2022). The concepts outlined by Barthes and Poststructuralism have informed my own photographic practice and my understanding of language and our contemporary use of visual culture. I see my art now to be in conversation with preexisting texts and sources that have been made available to me.

Understanding and embracing the polysemic nature of images within my practice was largely informed by The Death of the Author. I do not possess the subjects I photograph. I only situate myself in relation to them. They existed before the taking of my image and continue afterwards (Barthes, 2020). The mechanical permanence offered by the camera condenses experience in its temporary state of being. The resulting photograph exists as a mere representation, an avenue for conveying meaning. The elements within the photograph are then transformed into visual symbols that can be viewed and understood in an infinity of contexts (Chandler, 2020). My own way of seeing does not account for the entirety of my audience’s. In this way, I cannot present my images with a meaning that is correct or definitive (Berger, 1972). Barthes states that, “contemporary culture is tyrannically centred on the author” (Barthes, 1967, p. 1-2). Institutions of art and their value depend on the perceived “greatness” of the works that they house. Usually, selling the artists as the creative geniuses whose history, intention, and interpretations are regarded above all others. Despite having their own inspirations and sources, the artist is understood to hold the true meaning of their work. The artist becomes inseparable from the art. Barthes questions this generalised convention of originality by drawing attention to the “several indiscernible voices” existing within art. When we “assign a specific origin” (Barthes, 1967, p. 1) to a work, these voices are concealed, meaning becomes fixed, and there is no opportunity for discourse (Barthes, 1967). By criticising the common understanding of authorship, the artist’s interpretation becomes one of many. Personally, recognising intertextuality has meant creating work that responds to and directly references established culture. I am then able to address contemporary concerns in an active dialogue. This is most relevant in my photographic practice as visual culture becomes my material. As a painter works with paint, a photographer works with all that can be seen. The Death of the Author allowed me to be comfortable creating work that is open-ended and not bound to my own intention, recognising the audience as being as important as the artist’s contribution.

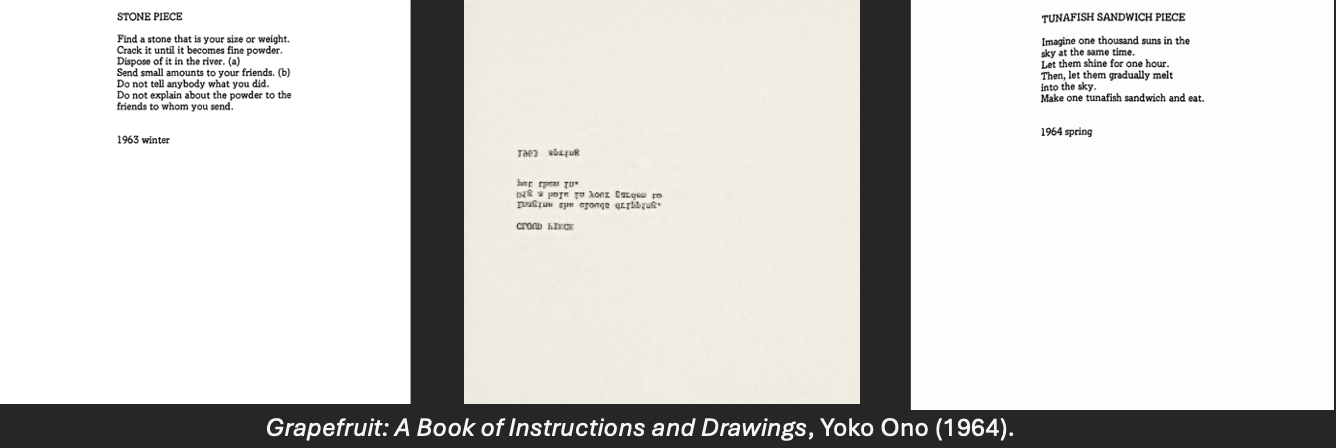

Although Barthes writes primarily about literature, his theories concerning authorship and interpretation are relevant to contemporary art. For example, Yoko Ono’s Grapefruit: A Book of Instructions and Drawings (1964). The work is minimalist in form, consisting of white pages with black text and no visual embellishment. Each page presents the audience with a set of directions to perform, such as “Imagine the clouds dripping. Dig a hole in your garden to put them in”. They invite the reader to participate in the creation of the artwork through their own imagination and action (MoMA, 2025). As a result, the artworks are openly co-authored by the audience, each reader bringing individual experience and interpretation as they engage with the prompts. Grapefruit engages with Roland Barthes’ theories as the work is open to infinite interpretations and meaning is made between the text and the reader, not in Ono’s own intention (Seymour, 2018). Ono and her work were prominent contributors to Fluxus, an avant-garde art movement that encouraged audience participation and believed art should be accessible to anyone. Fluxus artists sought to question the boundaries between art and everyday life, often using public art or collaboration. Both Ono and Barthes challenge the notion of the artist as a singular creative genius, instead positioning the audience as an active participant in the creation of meaning. In doing so, Ono’s Grapefruit not only illustrates Barthes’ theories but also extends them into the space of participatory and conceptual art.

While The Death of the Author informed my own practice within the arts, a comprehension of poststructuralist theory and semiotics radically transformed my perception of visual culture and contemporary art practices. The changes these concepts evoked in me were significant, as they encouraged me to question the structures of everything I had taken for granted. I began to recognise normalised ideology and the false dichotomies that are present within our culture (Foucault, 1994). In reading Michel Foucault’s Truth and Power, the relationship between sign and ideology became apparent. Foucault states that “each society has its regime of truth”, that is, “the types of discourse which it accepts and makes function as true.” (Foucault, 2001, p. 131). This discourse that is accepted, along with the aligning symbols, aids in integrating ideology and establishing social dynamics of power. The construction of a fixed truth allows for cultural hegemony. In that, society is not encouraged to question the present roles (Pandey, 2024).

Poststructuralism challenges the limitations of the structuralists’ truth. Seeing our experience as a system of signs and symbols that constructs our social reality. They reject the notion of any objective meaning and deconstruct social binary oppositions. Poststructuralism sees meaning as more ambiguous and nuanced, advocating for the individuality and subjectivity of experience as considered in The Death of the Author. I find denying the existence of a foundation of knowledge causes interpretation to become fluid and unstable. Meaning becomes contextual, as anything can be viewed with multiple connotations. The transition from structuralist theory coincided in art and culture with Postmodernism, an evolution of modernity (Fox, 2014).

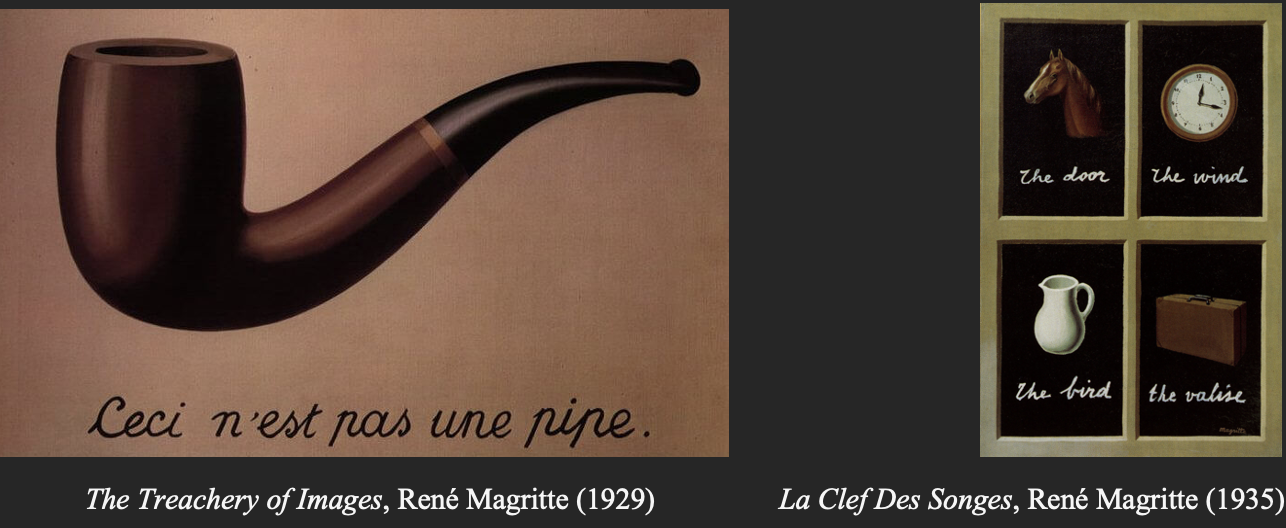

Postmodernist art adopts a similar scepticism of objective perception to Poststructuralism. Emphasising the plurality of perspectives through artistic expression. In addition to questioning Western philosophy, the movement often opposes traditional conventions of aesthetics and high culture. Postmodernist artworks are often obscure in form, involving abstraction and fragmentation. The cultural transition acted in response to the conditions of the time, often influenced by politics, psychology and philosophy. For me, Surrealism closely relates to the exploration of visual and linguistic relationships. Despite being primarily concerned with dreams and the unconscious mind, many artists acting in the movement explored the acceptance of our perceived reality. Magritte famously challenged linguistic structures in his painting, The Treachery of Images, 1929. The painting’s composition involves a depiction of a pipe, situated above the text, “Ceci n’est pas une pipe”. French for “this is not a pipe” (Magritte, 2009). He is correct in the statement, as it is only an image of a pipe.

Yet, in the way the paint is composed on the canvas, it points towards our constructed understanding of the object. In the same way, the word “pipe” is not in fact what it represents. In my interpretation, Magritte suggests that the relationships between words and objects have no natural connection but rather are arbitrarily related through our learnt experience. Magritte continued this exploration in a later painting titled La Clef Des Songes, 1935 (Moma, 2020). Referenced by John Berger in the first chapter of Ways of Seeing (1972). Berger frames Magritte’s painting in the context of a gaze. He begins by stating, “seeing comes before words…in the surrounding world; we explain that world with words, but words can never undo the fact that we are surrounded by it” (Berger, 1972, p.7-8). He addresses the “always-present gap” between what we see and what we know (Berger, 1972). Magritte’s painting is composed of a four-segment window frame. In each space, there is a visual depiction situated above text that does not align with the image. A picture of a horse labelled “The door”, a clock as “The wind”, a jug as “The bird”, and a valise as “The valise”. In their relationship to one another, we subconsciously connect them. Believing that they are somehow metaphorically or symbolically related. Both the images’ denotations and connotations bear a multitude of possible meanings. I find these paintings to be thought-provoking, while not moving the viewer in any direction. The open-ended nature of the composition forces the audience to construct their meaning, with reference to their own experience of each visual and linguistic symbol.

Studying The Death of the Author and Poststructuralist semiotics has deepened my understanding of how authorship and interpretation shape art and visual culture. However, in reflecting on these concepts, I find there are important limitations to consider when democratising authorship. The arts are often perceived as a field of subjectivity. However, when adopting the mentality that all is for individual interpretation, I believe it can undermine the expertise of the people working within creative institutions. Many artists are highly educated and have dedicated years of research to their given practice. Their ideas emerge from sophisticated dialogue with art theory and material. Ideally, the reception of their work should have a commonality in skillset. While I believe art should remain accessible and integrated into everyday life, a deeper appreciation perhaps comes with learnt experience of the iconological and historical contexts that inform the work.

I do agree that the notion of a creative genius as a singular originator should be dismantled, as it limits discourse and defines meaning. However, I feel there should still be recognition of an artist’s exploration and contribution to a field of research. As well as their experimentation and application of materials. Many established institutions continue to rely on authorship, and artists benefit from the institutions that house their works. I feel that an artist’s lived experience, and cultural background can have an important role in the perceived meaning and discussions surrounding a work. Rather than eliminating a notion of authorship from our interpretation, we should adopt a broader representation of artists within creative industries. I feel it is then important to consider the diverse conditions and expressions of different artists. It allows us to engage with art in a valuable way that exposes us to the individual experiences of others.

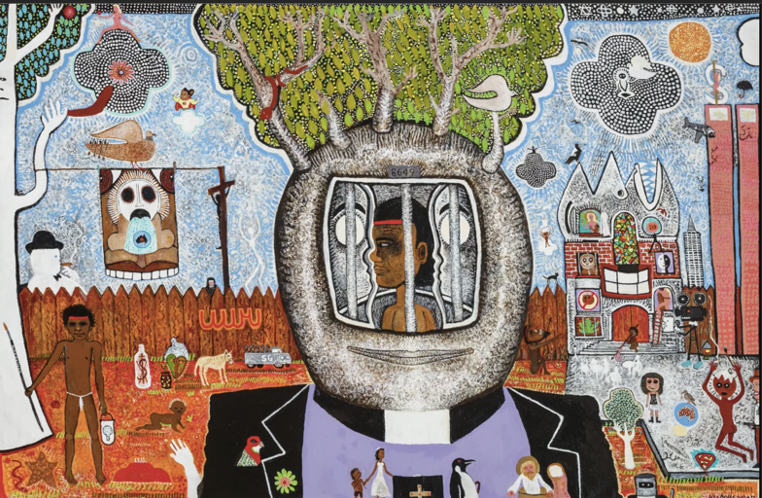

Brush with the Lore, Trevor Nickolls(1983)

One example of a work where I feel the artist’s experience is relevant to interpretation is Brush with the Lore (1983) by Ngarrindjeri artist Trevor Nickolls. The painting acts as a powerful commentary on Indigenous life in a contemporary context, exploring the coexistence and complex relationship between two cultures. As well as the lasting impacts of tragedies experienced by First Nations peoples. Nickolls’ constructed composition is deeply layered and features symbolic imagery throughout. At the painting’s centre is a personified Adansonia gregorii, or boab tree, depicted as a priest, with a portrait of the artist imprisoned within its mind. Surrounding this figure is a composite of recognisable symbols and imagery. Including Australian wildlife, Ned Kelly, a marijuana leaf and the 9/11 tragedy. The title Brush with the Lore uses the dual meanings of “lore” to reference both the history and narrative of Indigenous people, as well as portray the enforced “laws” and poor treatment of colonial authority (AGSA, 2020).

In relation to Barthes’ theory, Nicholls’ work demonstrates my hesitation with The Death of the Author. Nicholls references familiar iconography and reworks it to tell his own perspective. For me, this aligns with Poststructuralist thought as meaning remains multiple and invites an open dialogue. However, understanding Nicholls’ experience as an Indigenous person in a postcolonial Australia, in my opinion, adds to the significance of the work. For these reasons, I feel that Brush with the Lore both acknowledges identity and origin, while also embracing the plurality of meaning.

In conclusion, Roland Barthes’ text, The Death of the Author, has continued to shape how we view interpretation and originality in contemporary art practices. Emerging from Poststructuralism, Barthes challenged the author’s intention being central to meaning. Allowing for intertextuality and the recognition of sources. In Barthes’ theory, the reader has an active position in constructing the work’s meaning, as they read with reference to their own experience. The application of such theories within the arts means an emphasis on ambiguity and unstable interpretations, present in movements such as Fluxus and participatory art. The field of Poststructuralist semiotics and its influence on Postmodernist art have greatly informed my photographic practice. I now see photographs as appearances displaced and transformed into a system of symbols. I have learnt that our interaction with photographs is semiotic, rather than mimetic. This has led me to take images that emphasise their perceived connotations within my practice. I also embrace the role my audience has in constructing meaning through their engagement with my work. However, I feel there is a required balance between democratising meaning and recognising an artist’s origin. The artist’s identity often informs a deeper understanding of their work. In particular, the lived experiences of artists from marginalised communities. I believe the value in Barthes’ essay is the view that art is a collaboration between artist and audience, that lives to be in perpetual dialogue with itself.

Reference list

Barthes, R. (1967). The death of the author. [online] pp.1–6. Available at: https://writing.upenn.edu/~taransky/Barthes.pdf.

Barthes, R. (2020). Camera lucida. London: Vintage Classics.

Berger, J. (1972). Ways of Seeing. [online] London: Penguin. Available at: https://monoskop.org/images/9/9e/Berger_John_Ways_of_Seeing.pdf.

Berger, J. (2013). Understanding a photograph. London: Penguin Books.

Chandler, D. (2022). Semiotics : The basics. 4th ed. New York, Ny: Routledge.

Derrida, J. (1967). Of Grammatology. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Foucault, M. (1994). The order of things : an archaeology of the human sciences. New York: Vintage Books.

Foucault, M. (2001). Truth and Power. direct.mit.edu. [online] doi:https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/4884.003.0025.

Fox, N. (2014). Post-structuralism and Postmodernism.

Pandey, A. (2024). ON FOUCAULT’S ‘TRUTH AND POWER’. International Journal of Education, Modern Management, Applied Science & Social Science (IJEMMASSS), [online] 06(02), pp.62–65. Available at: https://www.inspirajournals.com/uploads/Issues/231221016.pdf [Accessed 9 Jun. 2025].

Seymour, L. (2018). An Analysis of Roland Barthes’s The Death of the Author. London: Macat International.

Moma.org. (2020). René Magritte. La Clef des songes (The Interpretation of Dreams). Brussels, 1935 | MoMA. [online] Available at: https://www.moma.org/audio/playlist/180/2390.

The Museum of Modern Art. (2025). Yoko Ono. Grapefruit. 1964. [online] Available at: https://www.moma.org/collection/works/127492 [Accessed 4 Nov. 2025].

Magritte, R. (2009). The Treachery of Images, 1929 by Rene Magritte. [online] Rene Magritte. Available at: https://www.renemagritte.org/the-treachery-of-images.jsp.

Curator’s insight - brush with the lore (2020) AGSA. Available at: https://www.agsa.sa.gov.au/collection-publications/about/australian-art/curators-insight-brush-lore/ (Accessed: 05 November 2025).